When there’s a lull (or what passes for a lull in the cacophony of 2020) in the news cycle, and attention turns to the long term effects of the pandemic, remote schooling’s impact on children is thrust to the fore. Fears of a “lost year,” of children falling irrevocably behind, and of an indelible loss of integrity in children’s educational journeys are rampant, and their validity can’t be ignored. It is harder to teach children who are sequestered in their own homes, experiencing collective and individual trauma, behind cameras they can easily turn off, with nearly the entirety of the world’s accumulated knowledge, opinions, entertainment, and imagery literally at their fingertips.

Children who are struggling to learn in a remote context, or who are distracted and disengaged, may be seeing grade-level material, but the well-founded and well-circulated fear is that they will have less access to effective ways of learning and therefore less retention. Furthermore, children and teachers are caught in a net of reinforcing feedback loops: children’s struggle to understand tasks or ideas communicated in the remote classroom leads to disengagement, which deepens their lack of understanding, which only invites further disengagement and heightens the draw of all that is instantly gratifying on the internet.

Even the most brilliant, creative, and innovative teachers may feel pressure to pull against this downward spiral by using conventional direct instruction to try to ensure that students’ foundational knowledge and skills do not erode, all the while working ever harder to reinforce expectations: you must turn in your homework; you must answer questions aloud; you must stay in the video call. As more class time is absorbed by these efforts at evoking compliance, the cognitive rewards students gain by participating fully in a shared learning community become eclipsed, further deepening disengagement.

To break these cycles that are suppressing both learners’ growth and the cultivation of thriving online communities, we need to choose a leverage point within our locus of control. We cannot limit distractions the way we would in the physical classroom, but we can apply plenty of leverage to the variable of engagement. Simply keeping students in the “room” and actively participating will do more to keep them from losing ground than any other intervention we might try. To do this, we need to provide students with meaningful connections to one another, opportunities to do work that is relevant and authentic, and learning experiences that build satisfying and substantive cognitive skills, habits of mind, and metacognition which cannot be replaced by watching Youtube or scrolling Wikipedia.

Now is the time to use hands-on project-based learning to meet student needs.

It can be done well in the remote context, in wide-ranging disciplines and by teachers of all levels of experience. Yes, it will keep students in the room. And, research highlighted in EduTopia shows that project-based learning increases retention and development of 21st century skills as compared to traditional direct instruction.

High-quality project based learning includes several key elements:

- There is a clear and authentic audience and purpose, real or simulated

- The topic or task relates to students’ lives and interests

- Students have voice and choice

- Outcomes are divergent; the creator is the most important factor in what is produced

- Students develop cognitive and domain-specific skills that can transfer to novel contexts

- There is structured support for planning and executive functioning, so students can set and meet challenging goals

- There are opportunities for collaboration and/or peer feedback

- Students iterate on their work

- Students reflect on their product, process, and learning

When we design instruction around these elements, students are connected to one another, to the work, and to their own learning in powerful ways.

When this project-based work includes the draw of fascinating STEAM materials and provides the opportunities for kinesthetic learning that are so easily lost in the remote classroom, it becomes that incredibly powerful lever for engagement.

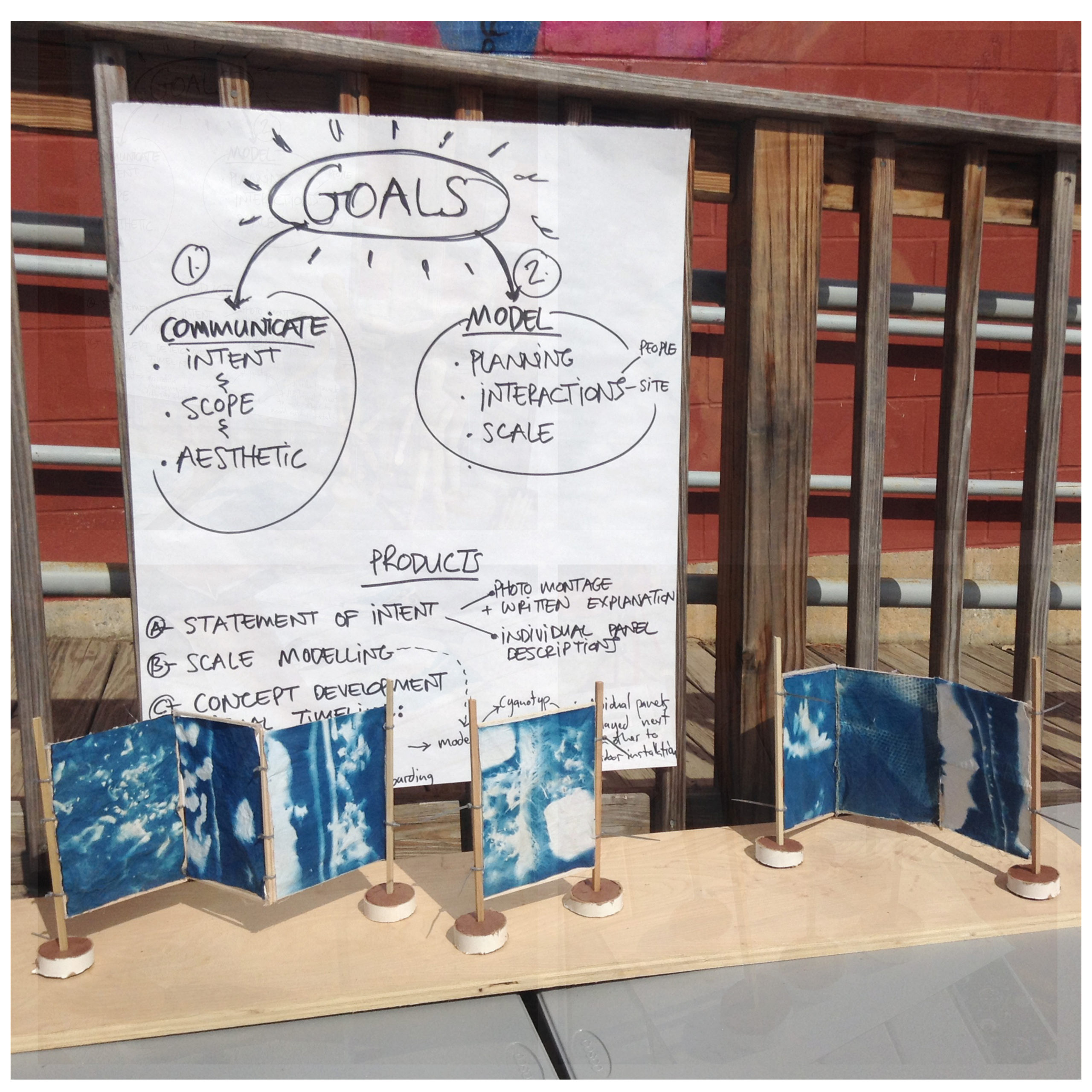

Students at Acera: The Massachusetts School of Science, Creativity and Leadership recently designed “mood masks,” lighted face masks to be worn during the pandemic when protecting public health also sometimes means giving up some of the communication that comes from our expressive human faces. Relevant to the moment and with a clear audience of anyone they encounter while wearing it, this project asked students to identify a specific purpose for their design, create and test a prototype, collect feedback from their colleagues, and iterate on a final product. At each stage of the process, students had clear visual representations of their immediate goals (more important than ever, in the digital learning space!) and support to identify the decisions to be made and factors to be considered. Within this clear and consistent structure, however, the decisions were always theirs, leading to diverse, beautiful, and functional final masks.

Students at Acera: The Massachusetts School of Science, Creativity and Leadership recently designed “mood masks,” lighted face masks to be worn during the pandemic when protecting public health also sometimes means giving up some of the communication that comes from our expressive human faces. Relevant to the moment and with a clear audience of anyone they encounter while wearing it, this project asked students to identify a specific purpose for their design, create and test a prototype, collect feedback from their colleagues, and iterate on a final product. At each stage of the process, students had clear visual representations of their immediate goals (more important than ever, in the digital learning space!) and support to identify the decisions to be made and factors to be considered. Within this clear and consistent structure, however, the decisions were always theirs, leading to diverse, beautiful, and functional final masks.

The Mood Mask project targeted learning goals in the STEM fields, around circuitry and programming, as well as in other domains: design thinking, empathy and emotional awareness, and communication skills. However, such a project might easily be a context for cultivating a wide range of other skills. Students in an English class might design a mask for a character that communicates their motives or range of emotions; students in a hybrid classroom might use it to solve the problem of struggling to be heard when asking for help; history students might design masks that would have changed the course of history if they had been worn by the right person at the right time. The parameters are infinitely modifiable around learning goals, student readiness, and available resources, but in any of these cases, students can only succeed if they have cultivated the STEAM and design thinking skills, built and applied their content-area knowledge, and made choices that were wholly theirs. In short, only active engagement and deep thinking will do.

At any time, in any classroom, student learning is deepened when connection, relevance, and big cognitive skills are at the fore, supported by strong executive functioning scaffolds, kinesthetic learning, and opportunities for students to witness and direct their own learning. In the remote classroom, they may be the difference between a lost year and the year when students find themselves.

Kim Machnik is the curriculum, instruction, and professional learning coordinator at Acera: The Massachusetts School of Science, Creativity and Leadership. She leads free professional learning workshops for public schools through Acera’s public outreach division, Acera Education Innovations (AceraEI).

AceraEI partners with public school districts to bring its pilot-tested Tools to Transform Schools to public schools everywhere, fostering the next generation of scientists, innovators, and leaders. For more information, visit aceraei.org.